The Bass Player Becomes The Steel Guitarist

Ho`olohe Hou continues to honor the musicians of the Hawaiian Room – the New York City venue which for nearly 30 years delivered authentic Hawaiian song and dance to exceedingly appreciative mainland audiences.

Our investigation into the Lani McIntire aggregation’s tenure in the Hawaiian Room has so far led us to believe that he worked this room – in various combinations – from 1938 until 1951. And we have made tremendous use of the discographical information to determine that Bob Nichols was the first steel guitarist with McIntire during this period, that Sam Koki was the second, and that Hal Aloma was the third, and that there was (possibly) a pair of mystery steelers during this period to boot. But who was the long-term successor to Aloma’s steel chair?

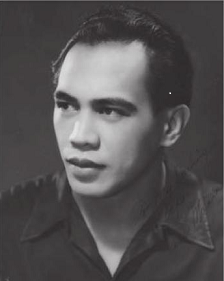

After a number of sides cut for budget label Sonora (the result of the American Federation of Musicians strike of 1942) with a pair of mystery steel guitarists in February 1945, it would not appear that Lani McIntire returned to the recording studio again for more than five years. This is perhaps another indication of the dwindling interest in Hawaiian music on the U.S. mainland during this period. But, fortunately, McIntire’s next sessions in March 1950 were again for a major label – MGM. And they featured his then current – and final – steel guitarist with a McIntire aggregation in the Hawaiian Room – Sam Makia. This is a story that requires us to rewind about a decade.

From the “Don’t Believe Everything You Read” category that characterizes so much so-called “documented” Hawaiian music history, the only entry on Sam Makia in any book on Hawaiian music – from the leading book on the history of the Hawaiian steel guitar – offers only one run-on sentence about this legend:

Vocalist and steel guitarist with Lani McIntire’s band at the Hotel Lexington NYC, then steel player with Johnny Pineapple’s band, then played bass with Ray Kinney at the same hotel.

All true, but completely chronologically backward. I previously wrote here about Ray Kinney’s first trip from New York City to Hawai`i in 1938 – not quite a year after the Hawaiian Room opened its doors – to recruit more talent from home. He brought with him on that trip steel guitarist Tommy Castro, falsetto singer extraordinaire George Kainapau, and multi-instrumentalist Samuel Kamuela Makia Chung. I have written also that Hotel Lexington president Charles Rochester did not merely insist on island-born-and-bred Native Hawaiians to work the room. He insisted that his employees live up to this ideal in every conceivable manner – including their names. In the well-researched Aloha America: Hula Circuits Through the U.S. Empire, author Adria L. Imada writes:

Yet most Hawaiian entertainers claimed racially mixed backgrounds with their names or by personal admission. Throughout his career, Ray Kinney referred to himself as the “Irish Hawaiian,” but because “McIntire and Kinney” sounded too Irish, the opening billing of the Hawaiian Room originally read “Andy Iona and His Twelve Hawaiians.” Chinese-Hawaiian Sam Chung began using one of his Hawaiian middle names professionally when he came to New York because “Makia” sounded more Hawaiian than his Chinese surname “Chung.”

Makia took this another step further, however: He changed his surname legally, as did his wife, Betty. And I should know: Despite coming to New York City in 1938 solely for the promise of fame and fortune the Lexington Hotel’s Hawaiian Room held in store, unlike most of their friends and revue-mates in the Hawaiian Room who eventually returned to their island homes, the Makias stayed in New York for the rest of their lives and were friends of my family until their passing. Sam took my father – another budding steel guitarist who went professionally by the name of Tomi Dinoh (and who took Sam’s lead by changing his Filipino birth name to something more Hawaiian-sounding for the stage) – under his wing, performing together frequently in the early part of my father’s Hawaiian music career in the 1960s. In my later years, I would sing while Betty danced hula for me countless times at gatherings of Hawaiian family and friends – her favorite the hula standard “Aloha Kaua`i.”

Because Kinney brought sterling steel player Castro to NYC with him, Sam instead made his Hawaiian Room debut on upright bass – making the earlier documented account above chronologically inaccurate. But by the mid-1940s, after the departure of Hal Aloma (circa. 1948), Makia would become Lani McIntire’s resident steel guitarist and continue in this capacity until McIntire’s passing in 1951 and beyond.

I have written here previously that Hawaiian music once comprised the majority of records sold on the U.S. mainland and represented three out of every five songs heard on U.S. radio. However, by the mid-1940s Hawaiian music had begun to wane in popularity. This – plus a temporary recording stoppage sparked by an American Federation of Musician’s recording strike – likely account for the reality that McIntire did not make a recording between February 1945 and March 1950. But when he did, unlike the previous small group session, McIntire brought the entire big band along the ride – a last hurrah for this era in Hawaiian music. The sessions at MGM’s New York City studios resulted in the four-disc, eight side 78-rpm collection (later reissued as a 10” LP) entitled Hawaiian Nights. Here are a few of my favorites from that 1950 MGM issue.

Click here to listen to this set by Sam Makia with Lani McIntire as you continue to read.

Sam trades bars with the saxophones and the celestes on the instrumental break in “Hawaiian Nights,” with lead vocal by Lani McIntire. On “Aloha Eyes,” the arrangement doesn’t leave much room for Sam except in the intro and ending (the arranger opting to punctuate Lani’s lead vocal with the celeste since metaphorically their sound probably speaks more to the “eyes” referenced in the song’s title). But on “Puanani,” Sam takes a long glissando into harmonics (often referred to as “chimes” because of the bell-like effect that steel guitarist achieves) in the second bridge and further accents Lani’s vocal with still more chimes. In this collection comprised entirely of ballads, the steel guitar was clearly intended to play a supporting role – which Makia does most tastefully. But in this era when the music was still heavily arranged, it is difficult to know which of the ideas emanating from the steel were notated on the chart and which came out of Makia’s head and through his hands.

Regrettably, the arrangements for these sides do not give Sam the opportunity to stretch out in the jazzy way that previous arrangements permitted Hal Aloma. In reality, Makia and Aloma were great friends who would go on to perform and record together in the post-Hawaiian Room era. Those who have heard these later recordings find their playing styles to be virtually indistinguishable. At some point we will revisit the lives and work of both Makia and Aloma in the New York days that would follow in the wake of dramatic changes at the Lexington Hotel.

Contradicting the aforementioned documented one-sentence account of his life one last time, Makia would go on to play steel guitar with the Hawaiian Room orchestra led by Johnny Pineappleafter Ray Kinney’s death – making Makia the only steel guitarist to remain in the Hawaiian Room after its leader departed.

Next time: What followed the end of the Lani McIntire era in the Hawaiian Room…