The “Lost” Mona Joy Album

Ho`olohe Hou continues to honor the musicians of the Hawaiian Room – the New York City venue which for nearly 30 years delivered authentic Hawaiian song and dance to exceedingly appreciative mainland audiences.

Researching the musicians who made the Lexington Hotel’s Hawaiian Room famous across the country and around the world has led to the unraveling of one mystery after another. But it also leads back to an unsolved mystery which – for me – dates back more than 20 years.

My passion for the music of Hawai`i was fostered in the bins of the once numerous used record stores that littered New Jersey, Philadelphia, and New York City. In the digital era, many believe that anything worth hearing that has ever been laid down in a recording studio would eventually see the light of day again as a CD or an MP3. But not so. Record companies are revenue-generating enterprises. They look to remaster and re-release music they can sell. And Hawaiian music does not sell (at least, on the mainland, not as it once did). And even in the rare case where a record company – or even just an interested individual – desires to fund the re-release of a recording they feel worthy, the master tapes may be lost or destroyed. And so, for Hawaiian music fans, our first – and last – resort has pretty much always been the dying art of “crate-diving” (or rummaging through bins of musty, moldy old records).

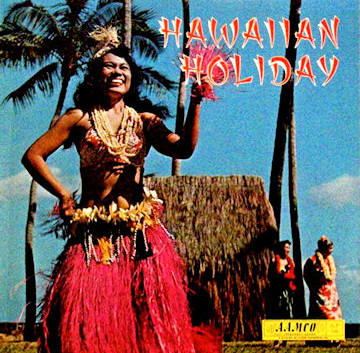

I have a pretty good memory for all things relating to Hawaiian music (and an advanced directive that the plug should be pulled when I can no longer tell you who played steel guitar on a particular recording). So I can tell you that it was in my late teens – right after I got my driver’s license – that I found myself “crate-diving” in one of the great used record stores (now long gone, like so many others) in the town of Pennsauken, NJ. I found a record that almost any other Hawaiian music lover would have passed up since the album cover smacked of the “cheese” that was becoming the hallmark of Hawaiian music made on the mainland since the legends – such as those of the Hawaiian Room – left the East Coast to return to their island homes. The album – simply entitled Hawaiian Holiday – boasted a cover featuring only a single hula dancer butdressed in Tahitian garb (a visual indication that these producers knew nothing about Hawaiian music). But, more telling still, the names of the artists was deliberately withheld from the front album cover – another almost sure sign that this record was made by nobody anybody cared about and that the music would be about as inauthentic as one could imagine it to be when the dusty grooves are spinning virtually on the platter inside one’s head.

But this was just the kind of record I always invested in – not too much a gamble at a whopping $1. And so I brought it home, placed it lovingly on a real turntable, and put the much-too-expensive-for-my-age-for-a-guy-who-makes-all-his-money-playing-music needle in the lead groove. And soon I understood that this might be the best $1 that I would ever spend.

The music that came out of those grooves could just as easily have been recorded in Honolulu as in New York City. But, as it turns out, the record was recorded in NYC. The gentlemen who produced the album knew what they were doing, however. The record label – Aamco (which I had never heard of, but which suspiciously was also the name of a local chain of transmission repair specialists) – I would not learn until years later was the brainchild of Carl LeBow, former General Manager of famed Bethlehem Records, a primarily jazz label popular in the 1950s for releasing some of the most well-loved and best remembered songs by such artists as Nina Simone, Chris Connor, and Mel Torme (artists I was well familiar with as I am a huge aficionado of jazz and the Great American Songbook). In short, LeBow had taste. In April 1958, he formed the budget record label called Aamco (located at 204 West 49th street in New York City) with the aim of releasing popular, jazz and international music. He named Ted Steele (who exited Bethlehem with him) as Musical Director and Vice President. Steele was well known throughout New York City as a radio and television personality for nearly 20 years. In short, Steele knew where to find the talent in NYC.

The formation of Aamco Records was announced in the May 19, 1958 issue of Billboard. According to the announcement:

Aamco Records will issue low-priced LP’s and eventually singles. First releases, which will be issued about June 15, will include a number of LP’s leased by LeBow from both Bethlehem records and Monogram Records”. (Monogram was not the label that released the early Chris Montez hits, but rather an earlier label run by Manny Werner that specialized in Caribbean/Calypso music.) Aamco released more than forty albums, with most having stereo counterparts.

But the label was doomed to fail. They sold albums for $1.49 each ($2.49 for the burgeoning “stereo” releases), so they didn’t make much on each sale. Despite the low margin, they might have been instead a volume-based business, but because they had no real hits, they didn’t sell a lot of records either. Within the first year, they had already jacked up the price of the albums, but it still couldn’t prevent them from going bankrupt two months later – less than a year and a half after launching operations. But not until – thankfully for Hawaiian music fans – they releasedHawaiian Holiday – historically and culturally perhaps the most important thing they would ever do (whether they knew it or not at the time) since they captured the end of a dying era of goodHawaiian music in New York City.

I was enthralled listening to Side 1 of Hawaiian Holiday when I finally decided to explore the album cover more thoroughly. Discreetly on the back cover the artists were listed as “The Catamaran Boys featuring Mona Joy.” Now, if I had seen “Catamaran Boys” on the front cover – coupled with the Aamco label – I would have decided without hearing the album that the group was comprised of mainland haole unknowns and the music would be inauthentic. But having heard an entire side before discovering the group’s name, I was convinced that the Catamaran Boys were an all-star aggregation from Hawai`i recording under a pseudonym (like Johnny Pineapple recording under the dubious moniker “Johnny Poi”) to avoid discovery because they were under contract to another label. “Catamaran Boys” could be a code name for any number of outstanding Hawaiian music artists as evidenced by the astounding and familiar sounds emanating from the JBLs. And, I understood one more thing: These outstanding anonymous musicians were likely living in the NYC area at the time the album was recorded. Because no Hawaiian musicians would fly from Honolulu to NYC to make a record for an as yet unknown record company – a record which, ironically, would receive little or no distribution in Hawai`i because of the economics of the situation.

Identifying the Catamaran Boys becomes still more of a challenge when you listen to the arrangements… The group relied heavily on their tight four-part vocal harmonies – reminiscent of The Invitations with their jazzy chordal approaches. But while the whole was clearly a sum of some very decent parts, it was impossible to identify any one of the voices because few of these gentlemen rarely took a vocal solo – the arranger choosing to treat the quartet as a singular voice. The exception is a few duets with Auntie Mona where one baritone with the ability to transition into a nifty falsetto truly shines. After more than two decades, I still cannot identify that voice. Finally, while the Catamaran Boys are also proficient on their various instruments – rhythm guitar, upright bass, `ukulele, and vibraphone – these, too, rarely take a solo. If there were a signature steel guitarist, for example, leading this band, most Hawaiian music aficionados would first be able to identify the steel player and then – based on that steel player’s professional affiliations – at least some of the rest of the band. But in this case, no dice.

But one thing I knew for sure: Mona Joy. Not merely a name affixed to the label to capitalize on her popularity and renown, the Mona Joy singing in front of the Catamaran Boys was the very same who had been serenading me on the cherished Luau At The Queen’s Surf LP for many years already. I’d know that voice in my sleep.

So as I wonder if Auntie Mona will remember the making of this album and who any of her session cohort might have been – a mystery which may be at long last resolved in just a few short hours – let’s enjoy a few selections from this long lost treasure…

First the opportunity to hear Auntie Mona sing “Ke Kali Nei Au” in a different setting than with Val Hao and the Waikiki Serenaders. (This 1958 recording made in NYC likely predates the Waikiki Records session back home by a few years.) Mona shines singing the wahine part, while the vocal quartet handles the men’s part together.

Auntie Mona then tackles – with the help of the aforementioned anonymous duet partner, one of the few solo male Catamaran Boys we will hear – the song Helen Desha Beamer wrote as a wedding gift for her daughter, “Kawohikukapulani.” Writing about Beamer here at Ho`olohe Houpreviously, I noted that because Auntie Helen was an opera singer herself, the songs she composed herself proved unusually challenging for anyone but the best trained singers to sing. Mona does Auntie Helen proud as do the vocal quartet who close the tune with their most jazzy chart.

The inclusion of “Ku`u Lei” is an indication that the group knows their Hawaiian repertoire as the song is a seldom recorded or performed composition from the pen of Hawaiian Room alum George Kainapau. Mona sings with the male vocal quartet whose vocal arrangement reflects what was happening back home in Honolulu with such vocal groups as the Kalima Brothers (with whom Mona would later work upon her return) or the Richard Kauhi Quartet.

The boys join in unison behind Auntie Mona as she regales us with the Harry Owens chestnut “Sweet Leilani.” Used in the 1937 film Waikiki Wedding, the original film arrangements for which were handled by Hawaiian Room alum Andy Iona, the song earned the Oscar for “Best Song” at the 1938 Academy Awards. The unison backing vocals by the quartet demonstrate that they were all pretty facile with their falsettos.

Written by Alice Everett and published by Charles E. King, “Ua Like No A Like” is also a staple of the Hawaiian repertoire that you would rarely hear mainland performers of Hawaiian music choose to perform. The song is again sung as a duet by Mona and the anonymous baritone with the sweet falsetto to rely upon when needed.

And the set closes with the other Hawaiian Wedding Song, “Lei Aloha, Lei Makamae” which – like “Ke Kali Nei Au” – is from the pen of Charles E. King. This will allow you another comparison/contrast with Auntie Mona’s version from just a short while later with Val Hao. (Frankly, I prefer this version better, the anonymous falsetto giving it everything he’s got – sweetly, gently, and typically Hawaiian.)

So will my fateful second meeting with Mona Joy resolve any of my decades-long mysteries? Perhaps. If not, at least this conversation-starter will allow me to atone for my previous stumbling in her presence. Were these Hawaiian Room musicians? If not, then who? And why did they have to remain anonymous? I have a hypothesis based solely on my ears (which are pretty damned good): The male vocal lead – the tenor with the lithe and supple falsetto – may, in fact, be none other than Hawaiian Room alum Ray Kinney who (according to discographies) returned to NYC throughout the 1950s to record with his old Hawaiian Room bassist (who would become a bandleader and steel guitarist in his own right, staying in NYC until his passing) Sam Makia. Kinney would be under contract to RCA around this time (based on the timing of his other record releases), and so he would not have been able to make a record for Aamco under his own name. If the mystery singer/bandleader isn’t Kinney, then I highly suspect it is a Hawaiian Room alum who worked under Kinney and who tirelessly studied his effortless vocal technique. If it is not Kinney, then it is an admirer who comes a close second.

Maybe I will know in a few short hours… Until then, here is to recovering and giving back to the Hawaiian music-loving world the lost recordings of the legends of the genre and – in this one rare case – sharing them too with the artist who made it all possible. Mahalo nui e Anake Mona for giving me a mystery worth living for…

~ Bill Wynne